Distributed File Systems - Scaling

DFS, HDFS Architecture and Scalability

Big Data - Where does it all come from?

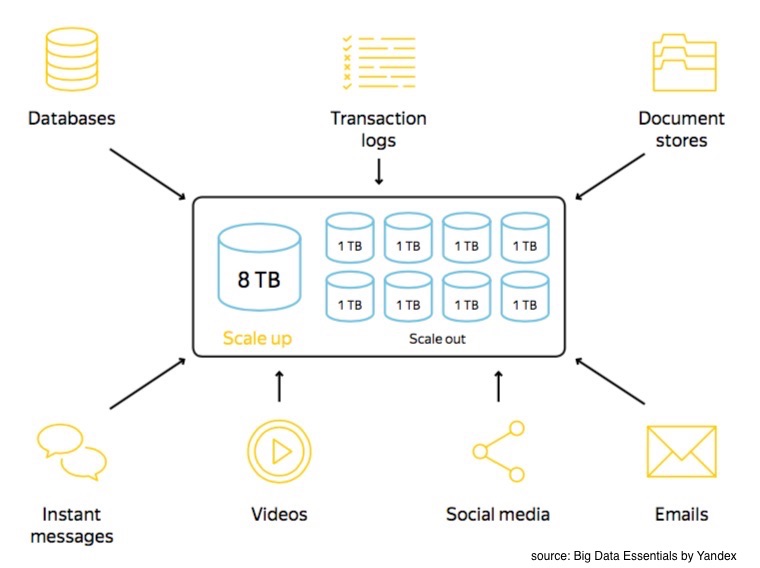

Data is everwhere - all from traditional sources such as databases, transaction logs, document stores and emails, to new sources being generated in the form in videos, social media, instant messaging, wearable devices, and sensors. So let’s say you’ve amassed a veritable treasure trove of useful data - a question arises. How should I store it?

Vertical vs Horizontal Scaling

You’ve got two options: 1) scale up, 2) scale out

The first option, is pretty simplistic - get a large capacity node (vertical scaling). Want to store more data? Get yourself a bigger and badder hard drive. This might work for a bit, until you realize that buying a 500 petabyte harddrive might not be realistic or safe. The second option is to store your data in a collection of nodes (horizontal scaling). Want to store more data? Get multiple smaller, cheaper hard drives. However, this can be tricky as each node will, on average, get out of service in three years. Each scaling approach has its own pros and cons.

Google File System - The birth of distributed file systems

In the early 60s, Google created a scalable distributed file system (DFS) with 3 key ideas:

-

Component failures are a norm rather than an exception. Because of this, all stored data must be replicated.

-

Even space utilization. Whether you have small or huge files, each are split into blocks of fixed sizes (around 100 megabytes) to ensure equal distribution of space usage on different machines.

-

Write once, read multiple times. Thanks to this rule, it dramatically simplifies the API’s internal implementation of the DFS.

Hadoop Distributed File System

Hadoop Distributed File System, or HDFS for short, is an open source implementation of the Google File System. From the implementation point of view, Google file system is written in C++, whereas HDFS is written in Java. Additionally, HDFS provides a command line interface to communicate with the distributed file system. In addition to binary RPC protocol, you can also access data via HTTP protocol.

Reading files from HDFS

When reading files from HDFS, you first request the name node to get

information about file blocks’ locations. These blocks are distributed over different machines

but all of that complexity of handled by HDFS API. As the user, we only see a continuous stream of data. Pretty convenient!

So if a data node dies and we retrieve the data from a replica, we don’t care as long as the data flows.

When reading files from HDFS, you first request the name node to get

information about file blocks’ locations. These blocks are distributed over different machines

but all of that complexity of handled by HDFS API. As the user, we only see a continuous stream of data. Pretty convenient!

So if a data node dies and we retrieve the data from a replica, we don’t care as long as the data flows.

Writing files into HDFS

When you write a block of data into HDFS, Hadoop distributes three replicas over the storage.

The first replica is usually located on the same node if you write data from a data node machine, otherwise it’s chosen at random.

The second replica is usually placed in a different rack.

Finally the third replica is located on a different machine in the same rack as the second replica.

When you write a block of data into HDFS, Hadoop distributes three replicas over the storage.

The first replica is usually located on the same node if you write data from a data node machine, otherwise it’s chosen at random.

The second replica is usually placed in a different rack.

Finally the third replica is located on a different machine in the same rack as the second replica.

These data nodes form a pipeline as your first client sends packets of data to the closest node. This node then transfers copies of packets through the pipeline. When the packet is received at all data nodes, the nodes send back acknowledgement packets. However, say if something goes wrong, then the client closes the pipeline to mark and replace the bad node so a new pipeline will be organized. HDFS takes care of all this complexity behind the scenes.

And because data nodes act as a state machine for each file block, whenever a data node in the pipeline fails, we can be sure that all the necessary replicas will be recovered while any unneeded nodes are removed. We’ll go into the details of this state machine later.

This is only a brief overview of the architecture and scalability issues around distributed file systems. Next post, we’ll explore the topic of HDFS recovery process more in depth.

(continue to part 2, Distributed File Systems - Recovery Process)

Sources:

White, Tom. 2014. Hadoop: The Definitive Guide. O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Dral, Alexey A. 2014. Scaling Distributed File System. Big Data Essentials: HDFS, MapReduce and Spark RDD by Yandex. https://www.coursera.org/learn/big-data-essentials